A cooperative, community-led solution for food insecurity in West Charlotte

By Mae Israel

After decades of being shunned by traditional corporate grocers rushing to expand elsewhere in the city, leaders in predominantly Black neighborhoods along West Boulevard have a new hope: that they finally will get a full-service, community-owned grocery store only minutes from their homes.

The optimism comes after failed promises and rising prosperity that never quite seemed to make its way from the glittering new skyline to the streets of West Charlotte. Residents and researchers worked this year in a new partnership with UNC Charlotte and Johnson C. Smith University, funded by Mecklenburg County, to create a viable plan to establish a pair of new food retail businesses in their neighborhoods.

“The work has been done,” said Rickey Hall, board chair of the West Boulevard Neighborhood Coalition. He’s spent years improving healthy food options for residents in an area designated as a food desert. “Now it’s time to get beyond talk. It’s time to stop questioning the community’s capacity, and let’s get this done.”

After nearly nine months of research, evaluation and community engagement, the collaborative group — hosted by UNC Charlotte’s new Community Innovation Incubator — is recommending the establishment of two for-profit, community-owned food cooperatives (co-ops) along major roads in the heart of West Charlotte.

The proposal calls for two distinct yet connected stores:

-

A flagship, 12,500-square foot “flagship” store at West Boulevard and Clanton Road, in an area that officials have long targeted for redevelopment.

-

A second, smaller , 4,400-square-foot “fast start” store would be located in a building owned by Reeder Memorial Baptist Church on Beatties Ford Road.

The group estimates it would take roughly $7 million to $8 million to establish both stores. They’re asking Mecklenburg County, which has ranked improving access to fresh, healthy food as a top public health issue, to start the process by investing $1.7 million for pre-construction planning, including land leases, architects and other costs.

Once the project receives county support, committee members plan to seek at least $6 million from private investors for construction and other start-up costs. Over the past few months, they have been soliciting support from local hospital systems and the YMCA of Greater Charlotte, which owns property near the West Boulevard and Clanton Road intersection. Federal grants and other investors would be pursued to help pay initial operational costs.

“There seems to be some real opportunity for significant investment,” said Dr. Byron P. White, Associate Provost for the Office of Urban Research and Community Engagement at UNC Charlotte. “I’ve been part of conversations where there is tremendous support.”

With public and private financial investment, as well as community support, the study committee estimates both stores could be operating within two years. The “fast start” co-op would allow for fine tuning operations while the flagship store is under construction on West Boulevard.

“Reeder has facilities and land that we are open to seeing repurposed in a way that would better facilitate the mission of our church and have a greater impact in the community,” said Rev. Thomas Farrow Jr., pastor of Reeder Memorial Baptist Church.

A history of disinvestment

In the neighborhoods along West Boulevard, many residents don’t have cars and rely on public transportation. No full-service grocery store offering fresh produce and fresh meat has served the area for more than 20 years. That leaves many residents to buy unhealthy, heavily processed foods at local gas stations and convenience stores — often at higher prices.

And while there are grocery stores along sections of Beatties Ford Road and in other predominantly Black, West Charlotte neighborhoods, such stores are significantly less plentiful than in other areas of Charlotte.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Quality of Life dashboard reveals the disparity: In 2018, less than 20 percent of the housing units in most West Charlotte neighborhoods were within ½ mile of a full-service grocery store. That compares to anywhere from 50 percent to 99 percent of housing units within ½ mile of a grocery store in higher income predominantly white South Charlotte neighborhoods.

People’s health is more complex than how close they are to a grocery store, but experts agree that access to fresh, healthy food plays a role, alongside factors such as income, insurance, education and lifestyle choices like smoking. The effects are obvious: In many West Charlotte neighborhoods, people’s average age of death is in their 60s.

In South Charlotte, residents commonly live into their late 70s or even 80s.

The Community Innovation Incubator study group found that West Charlotte doesn’t fit the income profile and other characteristics major grocers look at when they determine where to place their stores. But the study ultimately concluded the community needs to do more than simply lure a Food Lion or Harris Teeter to West Boulevard.

Instead, the study group proposed community-owned, co-op stores, operated by a board and a professional manager, which would play a unique role in the neighborhood and the city.

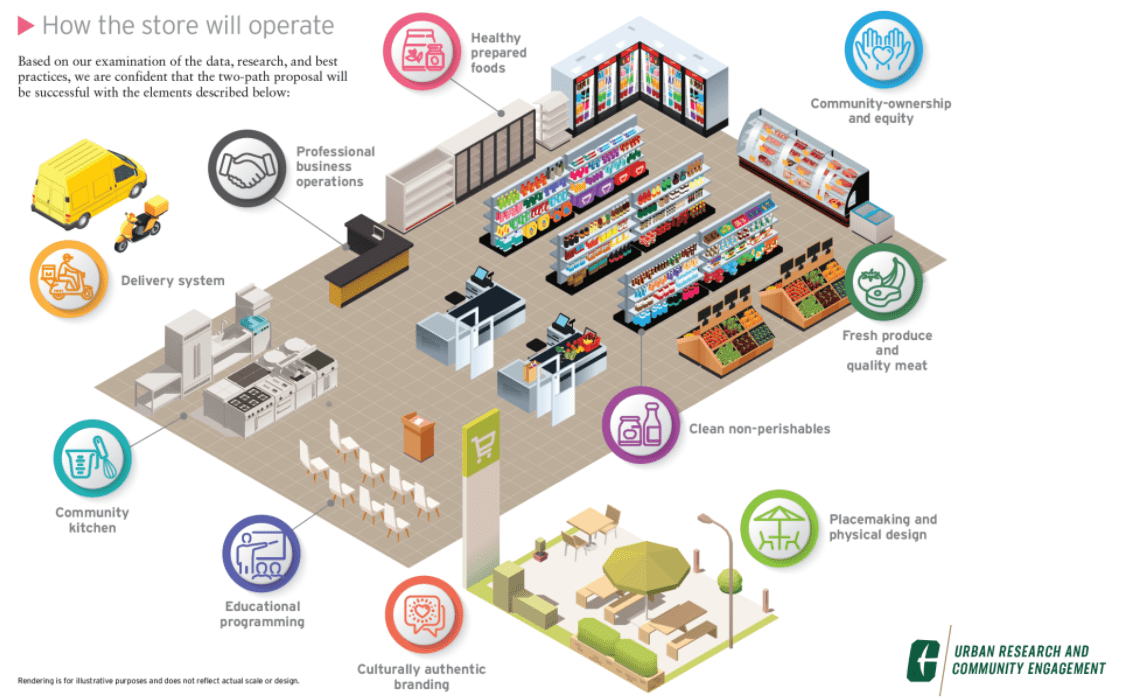

These stores would generate jobs and promote wealth-building for employee owners and community members. The co-ops would also provide a community kitchen for entrepreneurs, meeting space for local groups and programming about nutrition, health and wellness. The co-ops would also create a distinctive cultural identity, lifting up Black culture and achievements in a fast-changing part of Charlotte, that the study group hopes would attract a diverse group of shoppers.

Most importantly, the stores would provide fresh, affordable and healthy food in neighborhoods where many residents do not have cars.

A new model of community engagement

The West Charlotte food retail committee members are part of a new initiative, known as Community Innovation Incubator, in which West Charlotte residents and university researchers worked as equal partners to develop the proposal.

While residents have been working for years to improve food access in their neighborhoods, the university offered expertise in compiling and analyzing data, facilitating engagement, store design and other areas. The committee’s goal was to develop specific proposals that could become reality, rather than generate a wish list.

“I think the process has gone well,” said J’Tanya Adams, founder and executive director of Historic West End Partners, which promotes commercial development along Beatties Ford Road. “The matching of wits has been the part I like the best, the collaboration.”

Participants openly debated their ideas, worked together to research the best strategies, visited another food co-op in Raleigh and collaborated via Zoom and in-person. The committee’s work focused on one overarching question: What type of food retail business would best serve the West Charlotte community and be economically viable?

A Co-Op, Not a Traditional Grocery Store

Efforts to attract Harris Teeter and other stores to West Boulevard over the past two decades have failed. Economic studies reviewed by the committee show that low incomes in the area don’t meet criteria for most traditional grocery stores — and business strategies of these stores often don’t address many of the community needs.

Grocers don’t usually consider unearned sources of income, such as SNAP and WIC benefits, when they’re deciding where to put new stores. But an analysis by UNC Charlotte researchers showed that if those benefits are included in the buying power of residents, a co-op would be economically viable.

Support for a possible co-op has been percolating for several years. A 2018 plan by Inlivian (formerly the Charlotte Housing Authority) endorsed a co-op on West Boulevard. A city market assessment in 2019 recommended a co-op as a viable strategy, and Charlotte’s Center City 2040 Vision Plan lists a co-op as an option for the area.

In addition, the West Boulevard Neighborhood Coalition has worked on plans over the past few years to develop the Three Sisters co-op, named in honor of female community leaders in the area. The effort has received strong neighborhood support.

‘Fresh food access is a human right’ — Meet some of the people seeking change in West Charlotte

During its evaluation, the study group reviewed nearly 20 food retail enterprises across the country; most were co-ops launched with public and private investment in economically-challenged areas facing food insecurity. These co-ops include the Carver Neighborhood Market in South Atlanta and a planned community-owned store in Flint, Michigan, which the state’s governor announced a few months ago will be launched by state and local funds.

Discussions have already begun with potential suppliers for the West Charlotte co-ops, including Freshlist, a local aggregator that buys food from area farms, and Westside Meats, a Black-owned business. Charlotte City Center Partners have agreed to facilitate grab-and-go prepared food products from local businesses.

More than a Place to Buy Food

West Charlotte committee members insisted from the beginning that any proposed retail store should be community-owned and operated, even with outside investment.

“We need to say this is a social justice imperative,” committee member Debra Terrell, associate professor of psychology at Johnson C. Smith University, said during one of the sessions.

Many residents along West Boulevard and in other West Charlotte neighborhoods are struggling with chronic diseases such as high blood pressure and diabetes, in many cases caused by the lack of easy access to affordable fresh food and produce as well as healthy prepared foods.

One study conducted in part by the Centers for Disease Control, for example, shows that 41.9 percent of the adult population in the West Boulevard 28208 zip code has high blood pressure compared to 31.5 percent in Mecklenburg County.

Committee members agreed that a co-op should offer a holistic approach to the area’s issues, going beyond food access to offer educational programs and a community kitchen that would not only be used by the store personnel but by entrepreneurs developing food businesses.

“In this relationship, the government has to acknowledge the community is the driver and the government is the supporter,” said Hall. “It’s about the building of wealth. It can’t be somebody doing it for you.”

Just as importantly, according to committee members, is creating a co-op that brings a cultural perspective to Charlotte’s food landscape. An authentic, local food experience would attract not only West Charlotte residents, but residents from other areas of the city.

It would be a food store, the committee wrote in its report, which would be positioned as “bringing equity to West Charlotte through access to healthy food and a celebration of Black culture.”